Women in the Mahabharata, Part 1: a different Perspective

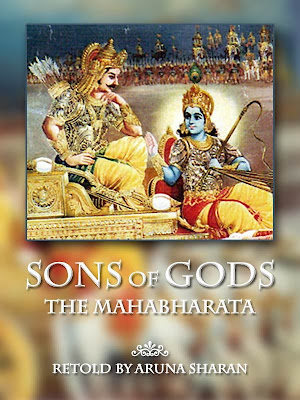

A few days ago, Hindu Blog posted an interview with me on Sons of Gods. A couple of the questions concerned a subject I was planning to write about in the near future, so let’s see what I said there:

Who do you think is the most tragic woman character in the Mahabharata?

The Mahabharata is a book about men, yet the few female characters are powerful indeed: the goddess Ganga, the Pandava’s mother Kunti, the Princess Amba, and of course the Pandavas common wife, Draupadi. Of them all, I find Amba the most tragic, as well as the most interesting, and I tend to identify with her.

As a woman, how do you see the treatment of women in Mahabharat? Is your view reflected in the book?

When we consider the women in the Mahabharata and their treatment, it’s important not to see them through the prism of Western feminism. This is a story set in an age and a place far removed from our own world. Different standards were valid in that age, and it wouldn’t be fair to speak of “repression” and “subservience” in that context. Yes, the Mahabharata is a story dominated by men. Yes, all the great heroes are male. And yes, there are only a few women, whose roles are mainly that of wife and mother. Yet, how powerful they are in those roles!

There’s the goddess Ganga, who dictates the terms of her marriage to King Santanu; there’s Gandhari, the mother of Duryodhana and his 99 brothers, who, after all the leading statesmen and wise councillors have pled in vain for peace, is summoned to the court to give the final word: as mother of the Kauravas, her wish is—or should be—final, and obeyed. Kunti is revered by her five sons, the Pandavas, to the extent that a word of hers spoken in jest is taken as an absolute command. And Draupadi: it’s for her sake, to restore honour to her, that the entire war is fought.

There remains only Amba, who is cruelly wronged by Bhishma near the beginning of the story; but I love the way how, after she experiences the most bitter shame and dishonour, she rallies her forces, decides on revenge, and focuses all her energy and her will on executing justice on Bhishma—even if she must die and be reborn again and become a man in order to do so. Amba is without doubt the very first transgendered character in literature; but even in a man’s body, she remains a woman, and it is as a woman she engages in battle against Bhishma. In Sons of Gods I’ve tried in a small way to honour Amba; yes, she makes mistakes, but in the end truth wins out.

And then there is Draupadi, the Queen of them all. She's so important she gets her own blog post, here.

We must remember that in Hinduism, the so-called female attributes of selflessness, forbearance and gentleness are seen as positive, whereas the so-called male characteristics of assertiveness, domination and control are considered negative, being traits of the ego that must, eventually, be surrendered to God.

Siva and Shakti, male and female energy, are seen as two halves of a whole, each valuable in its own right, each needing the other as a complement. God can be mother as well as father, and the Mother is, finally, divine. Ideally, women are seen as the invisible backbone of society; it is that backbone that holds society upright, and when it falls, so too, according to Hindu thought, does society. Of course this ideal, humans being as flawed as they are, is seldom realised, and women all too often trodden underfoot in India as everywhere in the world. But it is there, a goal to be aspired to.

In Sons of Gods I’ve tried to get under the skin of the few women, so that the reader understands their inherent, though perhaps quieter, strength.

The trouble with “getting under the skin” of the female characters, of course, is that to do so with every one of the women, and do so thoroughly, would have extended the whole book by a couple of hundred pages, which would defeat the whole purpose of a condensation. And so I was reduced to giving just a glimpse here and there into the inner life of the women: Kunti, when she summons the Sun God in the prologue. Amba, when she is disgraced by Bhishma and seeks revenge. Again and again, Kunti’s feelings for Karna: just a sentence or two that reveal the depth of her love for him.

Comments

I am also obsessed with Karna and have just published on Kindle my novel, "Loved By The Sun".

In my novel there are six stories in one and only one of them concentrates on the Mahabharata,as it is a progression of rebirths emanating from that great tale.

My book is not exactly a retelling of the whole Mahabharata but it does that by the fact that my main character is a lay person, a horse trainer, who comes under the wing of Karna and fights with him on the side of the Kauravas and is therefore told from the point of view of the so called bad guys.

In reading about your book I only wish I had had it before I started writing mine. You seem to have provided exactly what was now needed for the modern reader. I am also sure that you need feel no qualms about altering the story as the story has already been altered many times to suit the views and religious prejudices of each translator down through the ages.

I now believe that everyone should insert themselves into the Mahabharata and either tell their story through it or at least imagine themselves as one of the characters.

Thank you.

http://www.amazon.com/Loved-Sun-Mac-Nicolson-ebook/dp/B014JQW6K2/ref=sr_1_36?ie=UTF8&qid=1441012960&sr=8-36&keywords=Loved+By+The+Sun

Names of Lord Shiva