What is Dharma?

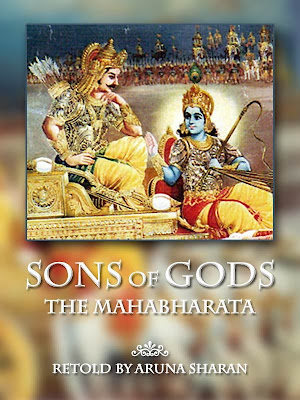

In Sons of Gods I’ve generally avoided Sanskrit terms. One of the exceptions, however, is the untranslatable word dharma; a concept that simply does not exist in the West.

Put simply, dharma is a composite of many concepts. It includes the idea of duty, righteousness, right action and inner attitude; and yet it is more than the sum of these parts. To act within dharma is to do the right thing, right now, taking into consideration all aspects of that action, past, present and future, as well as individual temperament and needs, and the needs of others affected by that action; and to do it free of anger, resentment or greed.

The Indian mind, for a Westerner, is complicated. There is no "right" and "wrong"; everything is subjective, yet not in the modern, Western sense, which centres on the fulfilment one’s own needs and desires as long as they don’t infringe on the well-being of others. Dharma is not about doing whatever you want, or fulfilling your own desires. In fact, acting within Dharma quite often means the denial of one’s own desires, and sometimes, even, the acceptance of unfavourable circumstances. It might be best understood under Reinhold Niebuhr’s "Serenity Prayer":

God, grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change, the courage to change the things I can, and the wisdom to know the difference.

But dharma goes beyond the Serenity Prayer, for it includes the concept of knowing and doing one’s duty, as well as one’s inner attitude towards that duty; the idea that selflessness, in the end, has a higher value than selfishness, and brings with it a higher final reward. Duty must be fulfilled without complaint and without whining: Just Do It, whether or not it results in the things you want. Dharma is the spine that holds society straight; without dharma it falls like an unsupported vine.

The idea of dharma as duty or right action stems from the belief that there is a natural order, a universal code or way of life and decision-making that keeps the individual in tune with the whole. Justice, social harmony and human happiness require that we learn to discern and live in a manner appropriate to the requirements of that order; eventually, it leads to Liberation, feedom from the incessant demands of ego. Whereas in the West we think of freedom as the ability to fulfill our wants and desires, the goal of dharma is to be free from desire itself, in order to recognise the inherent truth of who we really are. This is liberation.

Hinduism teaches that there are four ashramas, or stages of life through which each individual tries to fulfill the four goals of human life: kama (sensual pleasures), artha (profit), dharma, and moksha (liberation). Dharma is essential in all four stages; it can be seen as an inner compass through which we can measure and direct our actions. In our youth, our lives are mostly directed by that first two goals, pleasure and profit; but acting according to the principles of dharma will slowly and surely direct us towards the final goal, liberation; with that goal in sight, pleasure and profit are seen as transitory and trivial, providing no lasting satisfaction. They fall away naturally.

In the Bhagavad Gita, the core of the Mahabharata, Krishna teaches dharma as acting without attachment to the fruits of action; this, for the Hindu, is true strength. In the Mahabharata, Yudhisthira is the one character who embodies the concept of dharma; in fact, he is sired by the god of dharma, and because Dharma is the code by which he lives he becomes known as King Dharma. To the Western reader, Yudhisthira may appear too good to be true. He might seem goody-goody, regarded as too meek and mild: a wimp. Why does he not resist Duryodhana more? Why does he not take the advice of his brothers and destroy his enemy before the situation grows to a head? Why is he so calm and at peace when they are exiled for twelve years? What is wrong with him?

Nothing is wrong with him. Yudhisthira's strength is the still, silent strength that comes from within; that knows when to act and when to refrain from action, as exasperating and inexplicable as this may seem to the outsider. He is the Serenity Prayer personified.

But Yudhisthira is by no means perfect; he falls victim to his own vice, and even then his behaviour is too good to be true, resulting in the violation of Draupadi, and, finally to war. This is one of the lessons of the Mahabharata: there is no guarantee.

Leading a dharmic lif does not mean that from now on you will lie on a bed of roses. All too often the spiritual life is interpreted as other-worldly; people floating on some kind of a silver above the mud of daily life. That blessings will be strewn before youlike manna form heaven. That you will get all you ever wanted, just because "you are such a spiritual person".

No. It is struggle and effort all the way. Mistakes will be made; your own shadow will rise up to fight you at every corner. There will be forks in the road and you will make "nad" decisions, ones not in keeping with dharma.

But: you will persevere. You will learn form those mistakes and do better next time. You will mature and ripen and grow, and you will find a quiet, subtle, but deep fulfillment in doing the right thing just because it is right, irrespective of the fruits or pleasures it might or might not bring. Just like Krishna said.

You are responsible for your own actions, but you cannot control the actions of others. The only real choice you have, at any moment in time, is to be true to your own being.

Comments